What does it mean to press a like button regarding unpleasant content and images on social networks?

When I click “like” on a painful or disturbing post, I often ponder the following question: when a post addresses a harsh and troubling event yet reveals the truth, is it appropriate to like it on social media as a form of agreement, or is there a more suitable way to express our thoughts? Is it true to show approval for images of Gaza, Ukraine, Auschwitz, and other catastrophes in history, or should we express our views differently?

Why hasn’t Instagram given its users the option to dislike posts? While Facebook eventually added more reactions to capture feelings in 2015 after many years, the variety of options to express both positive and negative feelings is not balanced. Users can choose from six options for positive emotions such as support and encouragement, but only two for negative feelings like sadness and anger.

When we express approval for subjects such as war, inequality, racism, and corruption, does this mean that we support these issues? This creates a paradoxical situation between disastrous events and liking them. In other words, we show our good feelings when encountering bad circumstances even though we do not believe and confirm those negative events. In the book Critical Media, which critiques the concept of liking content on social networks, author Christian Fuchs describes “like” as an “ideology” and asserts that “the design of like button on social networks sites promote an ideology focused on being liked” (Fuchs, 2017: 269).

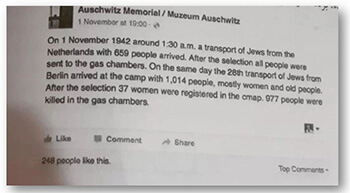

Fuchs discusses a post on Facebook regarding the Auschwitz tragedy and suggests that the people who clicked like were often not neo-Nazis but intended to share their disapproval; however, this action led to an increase in likes that ultimately benefitted Facebook by generating more advertising revenue and enhancing visibility for such humanitarian posts. However, Facebook gains more profit from those and turns significant and immaterial subjects such as humanity, climate change and peace into products. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and others do not provide users with the means to express their discontent.

Continuing this discussion, it’s crucial to recognise that favouring unpleasant content on social media reflects a dual nature and creates a moral quandary. On one side, users may utilise this action to demonstrate empathy and acknowledge significant issues; on the other, the limited options for expressing feelings can result in misunderstandings of users’ intentions. Liking is often the only reaction available, which may cause our engagement with these topics to be viewed as endorsement or indifference towards the pain of others.

Additionally, this scenario highlights the necessity to reevaluate the frameworks of social networks. These platforms need more sophisticated alternatives for users to interact with sensitive or distressing content, especially in situations that require disapproval, empathy, or critical support. The lack of diverse reactions creates a sense of uniformity. It leads to an unrealistic simplification in the tools of expression that fail to accurately convey complex emotions, compelling users to rely solely on a single “like,” even if it misrepresents their genuine feelings.

Moreover, from Fuchs’ viewpoint, expressing “likes” plays a significant role in promoting various goods and viewpoints. His perspective on social media platforms is legitimate, particularly as he aligns the essence of media with capital through a Marxist framework. It’s crucial to recognise that a rise in likes increases the probability of gaining visibility, thereby impacting content across political, social, and cultural areas. These concerns underscore the necessity of providing users with additional tools to express their feelings and views more accurately and subtly regarding social and humanitarian issues.

This trend was apparent during the Arab Spring[i] in 2011, where Facebook acted as a driving force for the movement, as well as during the Iranian protests from the 2009 movements[ii] to the 2022 protests, which were called the Women, life, freedom[iii] movement, where Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram aided in organising these events. (For more information, see the Networks of Outrage and Hope by Manuel Castells.) While in American and European contexts, social networks mainly operate as profit-driven multinational corporations, in nations with restrictive and authoritarian regimes, these platforms serve as venues for expressing diverse user voices and those of the silent majority who lack a voice in formal discussions.

Consequently, the social network dynamics in Iran cannot be comprehensively analysed through a singularly critical and global perspective that employs specialised concepts like commodification, consumer ideologies, and connections to capitalism. Instead, another aspect relates to the opportunities for activism and symbolic resistance, such as generating attractive content and presenting personal images on Instagram.

For additional insights, please refer to the following articles:

- Castells, Manuell. (2015). Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: Polity.

- Fuchs, Christian. (2017). Social Media: A Critical Introduction. London: Sage.

- Rezaei, M., & Pooraskari, M. (2016). Facebook and Voting Behavior: An Analytical Approach to Iran’s Presidential Election in 2013. New Media Studies, 2(5), 1-32. Doi: 10.22054/cs.2017.7003

- Koohestani, S., Alikhah, F., Ofoghi, N., & Hallajzadeh, H. (2023). From Ordinary to Microcelebrity: a typology of Iranian Instagram microcelebrities. New Media Studies, 9(33), 174-123. Doi: 10.22054/nms.2023.71996.1518

Notes:

[i] series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab countries in the early 2010s.

[ii] The protests of 2009 occurred in Iran due to the margins of the presidential elections and the victory of the candidate of the conservative party.

[iii] Protests of September 2022 as a result of the killing of Mahsa (Zhina) Amini, a Kurdish girl, by the morality police which is under the supervision of government’s security agencies.

Samaneh Koohestani holds a PhD in Cultural Sociology from Iran and is an independent researcher. Her research areas concentrate on digital media, celebrity culture, gender studies, and everyday life. In her doctoral dissertation, she examined the mediatisation of everyday life and the influence of internet celebrities in Iranian society. She is actively engaged in writing, translation, and research about socio-cultural issues, on social media platforms and public sphere. LinkedIn: Samaneh Koohestani.