Our Prime Minister’s sexual relationships hold no interest for me, but allegations of using public office to favour friends is of considerable public and sociological interest. As Mark Granovetter observed, it is not contracts but social relations that ‘are mainly responsible for the production of trust in economic life’, noting that, ‘the trust engendered by personal relations presents, by its very existence, enhanced opportunity for malfeasance’ (Granovetter, 1985: 491).

My interest in these issues intensified through research using freedom of information requests. Its focus was upon a £5million NHS prison health care contract won by Secure Healthcare Ltd (SHL) in 2007. Established with a Department of Health grant of £113,000, SHL collapsed with debts of £1.5 million two years later. When first raising questions about the contract as a NHS Non-Executive Director, official responses rejected any basis for concern. Following a NHS investigation, my own concerns were described as, ‘completely unfounded’, as, ‘the underlying reason for the failure of SHL were typical reasons for business failure’.

This unsatisfactory response received in my non-executive role – one which is intended to hold decision-makers to account – prompted a more systematic piece of research using FOIA. Disclosed information provided a very different picture (Sheaff, 2017; Sheaff, 2019). There is reason to reflect on why the obstacles I met as a non-executive became for me both an opportunity and a responsibility to research, allowing exploration of what Goffman called ‘dark secrets’.

Over time, responses to my questions moved from dismissal to total denial. This evolved into a questioning of my motives. A turning point came in April 2013 when a lawyer appointed by the NHS sent the following response to my questions:

‘You are not an investigator, regulator or statutory body and you have no standing from which to require anyone to co-operate with your lines of enquiry. None of these people are accountable to you. . . ‘I am in the process of drafting a Protection from Harassment letter to you regarding proceedings to seek an injunction against you.’

Two months later, I wrote in a diary note:

‘Looking back through two years of documents and correspondence, I see at the outset an almost naïve attempt to bring information to the attention of the authorities. . . What had appeared to be indifference now looked more like obfuscation. What I had assumed was ignorance began to seem like concealment. . .

I began to piece together a picture that no-one considered it to be their responsibility. . . Eighteen months after first raising questions, I had been able to establish through formal NHS processes little more than that many core concerns had not been investigated. I was advised it would not be possible to pursue this as the organisations were being abolished as a result of the Health and Social Care Act. . . . I now understand that it is the “clean up work”[i] that concerns me more than the original issue itself. More than that, I have felt angry that it has proved so difficult to have concerns taken seriously.’

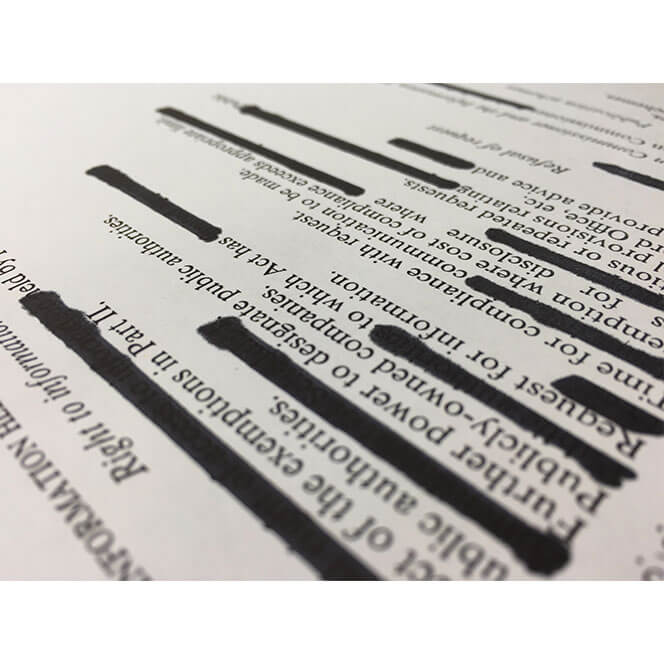

In 2018, of 19,270 FOIA requests to government departments and bodies that were withheld in full or in part, 12,175 were justified on one or other of 22 statutory exemptions. Of these, by far the most frequently used exemption, comprising 49% of the total, concerned ‘personal information’ (s40 of FOIA). One refusal to disclose information in my own research led me to complain to the Information Commissioner, who described the view of the relevant government department: “Whilst the redacted information relates to the data subjects’ public lives, disclosure into the public domain may cause damage to the professional reputation of the data subjects.”

More than a decade has elapsed since the House of Commons refused to disclose details of MP’s expenses, claiming it “would compromise the privacy of the MP”. This was rejected by High Court, which upheld a decision by the Information Commissioner that, ‘particular regard should be had to whether the personal data requested relates to individuals acting in an official as opposed to a private capacity’.

The boundary between ‘private’ and ‘public’ has long been a source of controversy and a focus for sociological analysis. ‘Making the private public’ was a goal of many early feminist critiques. In one appeal I made to the Information Tribunal, disclosure of an unredacted letter was refused on the grounds it contained ‘personal data, but the tribunal’s judgment noted my, ‘entirely legitimate quest for transparency and accountability’.

We live a in a period when public mistrust in those holding positions of authority is buttressed by scepticism towards information offered by public institutions. Coinciding with unprecedented technological opportunities to access information this generates wars over ‘truth’ that will not be resolved through transparency alone. But careful analysis of decision-making can reveal how social and institutional arrangements simultaneously contribute to error and to its concealment. My experience showed the unique and vital contribution sociology can make to interpretation in this area. Protection of privacy is a fundamental social requirement, but must not be allowed to protect those in positions of power from legitimate scrutiny and accountability.

References

Granovetter M (1985) ‘Economic Action and Social Structures: The Problem of

Embeddedness’, American Journal of Sociology 91(3): 481–510.

Sheaff, M. (2017) ‘Constructing accounts of organisational failure: Policy, power and concealment’ Critical Social Policy. 37 (4): 520-539

Sheaff, M. (2019) Secrecy, Privacy and Accountability: challenges for social research. Palgrave Macmillan.

Vaughan D (1999) ‘The Dark Side of Organizations: Mistake, Misconduct and Disaster’, Annual Review of Sociology 25: 271–305.

[i] ‘Clean-up work’ is a term used by Diane Vaughan (1999) to describe subsequent efforts to conceal organisational misconduct

Dr Mike Sheaff is an Associate Professor in Sociology at the University of Plymouth.