The Russia-Ukraine war and the ongoing negotiations on the possible resolutions of the conflict draw attention to the socio-political processes in both societies. If Ukraine is open to exploration by international scholars, Russia largely remains inaccessible to researchers from ‘Western’ Universities due to the geopolitical tension and complication of foreign affairs. However, while the big players contest for the domains of global influence on the grand chessboard, ordinary people continue to experience increasing inequalities on the ground, and sense their consequences in their everyday lives – struggling with and against them.

The location of the conflict is of great significance to investigating how class operates in post-socialist societies which historically formed different social structures compared to Western ones. This also raises other questions of ordinary people’s perceptions of inequalities from moral and symbolic viewpoints, as well as grassroots reactions to the social injustice taking place in neoliberal neo-authoritarian regimes where open protests are forbidden.

These questions form the basis of the current debate on the return of inequality, as Mike Savage (2021) frames it, focusing attention on its moral aspects. Social scholars suggest exploring the moral basis of social divisions utilising the concepts of ‘moral signifiers’ of class (Sayer, 2005), ‘lay perceptions of inequality’ (Irwin, 2018), ‘a sense of inequality’ (Bottero, 2020) and ‘a sense of social justice’ (Bikbov, 2007). Briefly, this moral turn in the studies of stratification allows a critical discussion about lay normativity, the moral ethos of ordinariness and multi-dimensional nature of inequalities, going beyond the difference in economic incomes.

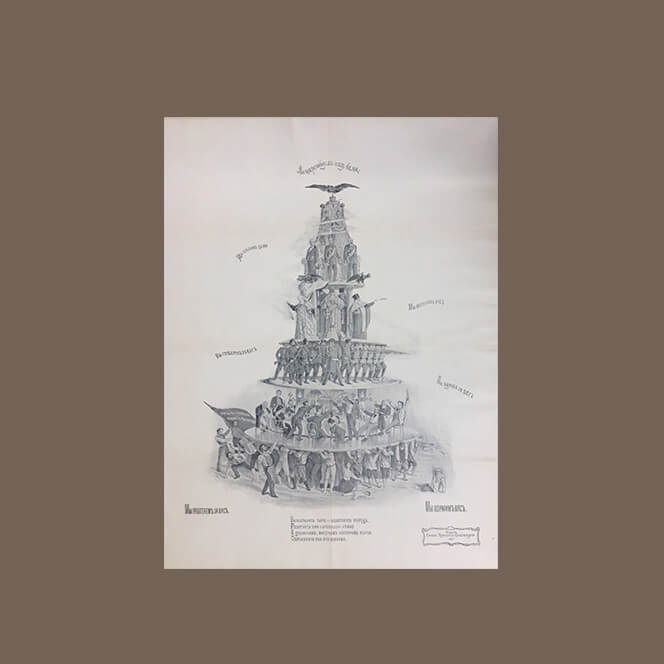

My recent article considers these issues, by specifically looking at how Russia-based workers and professionals express their sense of inequality through narrative strategies, which include compliance with the established order, inversion and subversion of power hierarchies. The article builds on the data collected through multi-sited ethnography, which included participant observation; thematic interviews with 50 residents of deindustrialising areas of Moscow and Yekaterinburg and three trade union activists from Moscow suburbia; and their 35 drawings of Russian society, visualising sensory perceptions of everyday inequalities.

The strategy of compliance with the established order is related to the depiction of society in the form of a hierarchised pyramid of enclosed classes, with the small elite and oligarchy on the top, large ‘all the rest’ entity at the bottom, and medium-sized ‘the middle class’ placed between the elite and ordinary people. Such pyramidal images of society demonstrate the top-down power dynamics in the neoliberal neo-authoritarian regime. Those at the bottom are perceived as rightless and suppressed, while those on the top are perceived as powerful and recognised.

Inversion of power hierarchy through irony manifests itself in drawings containing funny social portraits of poor people with brooms, old cellphones and cheap secondhand cars at the top, and rich ‘oligarchs’ in fashionable clothes with yachts and expensive cars having extra-ordinary, luxurious lives, appearing at the bottom. As Karine Clément and Anna Zhelnina (2020) explain, ordinary people employ narrative strategies of making jokes, ironic inversion and mockery of the authorities to resist social inequality in Russia. Such images show class divisions based on economic consumption and lifestyles, clearly visualising a gap between the rich signified as ‘indifferent’ and ‘bad’, making a living unfairly, and the poor morally viewed as ‘good’ and ‘fair’ making a living by doing hard work.

Finally, the narrative strategy of subversion of power hierarchy contains an explicit critical message about social injustice and inequality informed by what Cornelius Castoriadis terms ‘radical imaginary’ (1975) capable of producing social change through the power of creativity. Drawings of such a type visualise Russian society as divided between two antagonistic classes, the ‘greedy’ capitalists and the working classes, subdivided into ‘active’ and ‘passive’ factions. These images translate the ideas of trade unionism, civil society and grassroots struggles allowing ordinary people to accumulate power from below and ‘make a hole’ in the wall, which separates capitalists from workers, preventing the latter from getting higher positions. This Marxist vision of society as socially split between the rich and the poor is political. It suggests collective struggle as a way of dealing with inequalities.

Notably, the images of the second and third types do not contain the middle class, which, according to the explanations by research participants, diminished due to the economic turbulence. Altogether, the analysis of drawings and interview narratives has allowed me to argue that workers and professionals subjectively perceive Russian society as unjustly divided between rich and poor and consisting of separated social classes. This argument is situated within the debate on splits in Russian society, as Karine Cléments (2017) argues, and downward social mobility for workers compared to the Soviet era, as argued by Charlie Walker (2012).

In contemporary Russia, class operates as a regulator creating social divisions in society, which ordinary people navigate drawing on their sensory experiences of inequalities in everyday lives. Russia’s ordinary people are aware of inequalities and use various ways of overcoming them, relying on their social networks of horizontal cooperation and mutual support.

Everyday reactions to neoliberal challenges and inequalities are conditioned by the objective restrictions for open social protests produced by the neo-authoritarian regime controlling the population and violently supressing public disagreement. But this does not mean that all ordinary people passively accept inequalities. On the contrary, some of them re-codify inequalities in moral terms and do what they can do in the repressive contexts they live in.

What implications does this research have for the understanding of Russian society? The clear divide between the ruling class and ordinary people produces parallel realities, in which rich and ordinary people live and act separately, including the spheres of grand politics for the elites and everyday politics for ordinary people, as explained by Jeremy Morris (2025). However, one should explore further the effects grassroots everyday struggles against inequalities has on society.

Watch my video abstract my article, Researching Lay Perceptions of Inequality through Images of Society: Compliance, Inversion and Subversion of Power Hierarchies.

References

Bikbov, A. (2007). Social’nie neravenstva i spravedlivost’: Real’nost’ voobrazhaemogo: Risunki sovremennogo obshchestva v Rossii i Frantsii [Social inequalities and justice: The reality of imagination (drawings of contemporary society in Russia and France)]. Logos Journal 5(62): 162–208.

Bottero, W. (2020). A Sense of Inequality. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

Castoriadis, C. (1975). The Imaginary Institution of Society. Cambridge: Polity.

Clément, K. (2017). Social imagination and solidarity in precarious times: The case of lower class people in post-Soviet Russia. The Russian Sociological Review 16(4): 53–71.

Clément, K. and Zhelnina, A. (2020). Beyond loyalty and dissent: Pragmatic everyday politics in contemporary Russia. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 33: 143–162.

Irwin, S. (2018). Lay perceptions of inequality and social structure. Sociology 52(2): 211–227.

Morris, J. (2025). Everyday politics in Russia: From resentment to resistance. London: Bloomsbury.

Savage, M. (2021). The Return of Inequality: Social Change and the Weight of the Past. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Sayer, A. (2005). Class, moral worth and recognition. Sociology 39(5): 947–963.

Walker, C. (2011). Learning to Labour in Post-Soviet Russia: Vocational Youth in Transition. London and New York: Routledge.

Alexandrina Vanke is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow and a Research Associate on the project Deindustrialization and the Politics of Our Time at Concordia University, Montréal. Her expertise lies in sensory ethnography, qualitative methods and arts-based research approaches. Her research interest spans from critical social theory, class and inequality to everyday life, environmentalism and urban space. She is the author of The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia: Engaging in everyday struggle (Manchester University Press, 2024). X/Twitter: @alevan_alevan and Bluesky: @alevan.bsky.social