‘Roma Art’ – the self-described movement of modern day artists from a wide variety of Roma, Gypsy and Traveller heritages – is having a moment. Delaine Le Bas – a British artist of Romani heritage – has been nominated for the 40th Turner Prize (at Tate Britain until 16 February 2025). The Venice Biennale has housed various ‘Roma Pavilions’ since 2007, whilst Małgorzata Mirga-Tas was chosen as the official Polish representative at the 59th Biennale in 2022 – the first Roma artist to represent a country. Documenta15, the influential art show in Kassel, Germany, displayed its first ever group exhibition of Roma Art in 2022. These artists and exhibitions are bringing the triumphs and struggles of their communities to public visibility in diverse and extraordinary ways, even questioning what the phrase ‘their communities’ actually means and to whom.

I’ve observed three main ways such artists are changing the ways we see these minorities in public spaces, and ask what we can learn as academics. First, artists and activists create a relationship between old stereotypes and alternative narratives by taking objects, maps or dress associated with stereotypical ‘Gypsies’ and reworking them. Artist Damien Le Bas’ propensity for re-working maps, for example, draws on his own feelings of not belonging that also becomes about reclaiming a place in the world for Roma people. From an activist exhibition, ‘No Innocent Picture’, a young woman shows in one image how she dresses in her everyday life, and juxtaposes this with another image of how others might see her – as a mysterious, colourful fortune-teller. Thus different materials are brought together to make us ‘read’ the representation differently – disrupting the familiar to recognise the presence of real Roma people who have often been ignored or written out of collective cultures and histories.

The second way is the use of space to assert presence in public spaces – literally taking up huge amounts of physical space. Artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas exhibited at the 2022 Venice Biennale floor-to-ceiling hand stitched tapestry panels depicting women who have cared for her and inspired her, wowing audiences with the sheer scale of her work. Roma women are shown meeting, singing, drinking coffee, out in fields gathering potatoes, stitched in fabrics taken from their own clothes. The size of the work highlights both the space that these women occupy in the artists’ life, as well as giving a message about the space not normally afforded to such representations. Artist Nihad Nino Pušija also offers some huge images in his work Gladiators – but rather than Mirga-Tas’ celebration of community and Roma women, in this work Pušija reveals a vulnerability to his male subjects, as the unwavering gaze of these enormous photos of solo young Roma men in gladiator costumes is offset by the seeming vulnerability of their young bodies in warlike costumes, pictured alone.

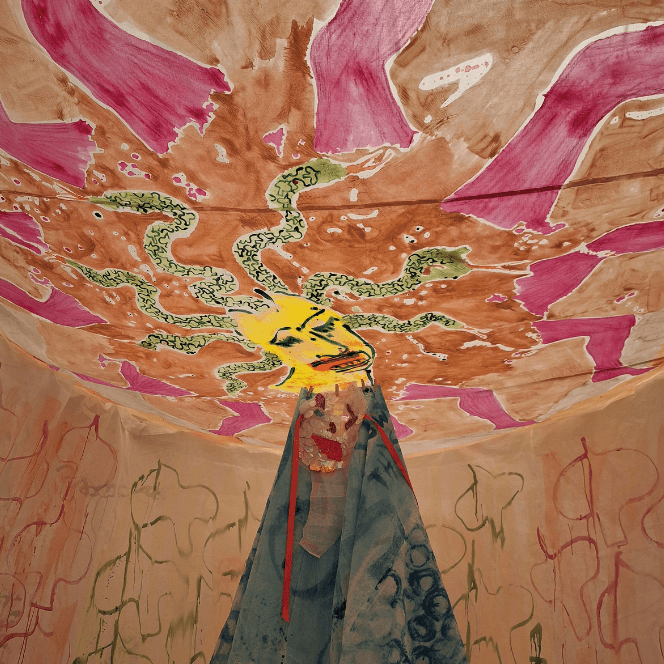

The depiction of Roma people in the artworks forms an important means to reimagine public spaces as inclusive. But it’s not as simple as just inserting something associated with ‘Roma’ into public spaces. This leads us to the third way artists are challenging stereotypes – by both destroying and reclaiming the idea of ‘being Roma’. Many artworks question what ‘Gypsy’ or ‘Roma’ or ‘Traveller’ means, to whom and why. Selma Selman in her performance Platinum (2021) at the National Gallery of Sarajevo, shows herself extracting precious metal from catalytic converters pulled from scrapped cars and creating a tiny platinum axe. As gender expert Jasmina Tumbas points out, Selman’s work both defies old clichés of Roma women as the femme fatale Carmen, whilst emphasising the hard labour typically carried out by Roma people. Delaine Le Bas’ Turner Prize nomination, ‘Incipit Vita Nova. Here Begins The New Life’ is a stunning example of the transdisciplinary, multi-media way she invokes the very political and private struggles she has as a feminist British Romani woman – something Gayatri Spivak has noted about her work as a type of theoretical staging.

These artists bring to the fore a question about labelling and authority – who has authority over what ‘Gypsy’ means and why? Roma artists from LGBTIQ backgrounds also question labelling by drawing on queer Gypsy subjectivity to address concerns with Roma invisibility. Used as a means to address all anti-Gypsyism, they ask what visibility means for Roma people. Artist Daniel Baker, for example, works with everyday objects (mirrors, wheels and colourful textiles) to explore how Roma visuality reflects and informs the lives of Roma people) whilst others question or defy gender and cultural norms whilst reasserting their own ‘Gypsiness’ (also see, for a few examples from many, the works of Diana Apsara, Juano Diaz, Mihaela Drăgan, Roland Korponovics, Cherry Valentine).

All three observations show how Roma Art assumes no authority over what it is to ‘be’ from a Roma heritage. Instead, the labelling is questioned through materiality, use of space and visuality. In this way the terms ‘Roma, Gypsy and Traveller’ are taken out of the essentialisms that have plagued their traditional counterparts. It’s not about ‘who’ or ‘what’ constitutes ‘Roma’. This is something we can all learn from – to foreground representations from people and communities with these experiences. In this example artistic representations are questioning the power of labelling and the associative histories of misrecognition instead of unthinkingly ploughing on with a project ‘about the Roma’. ‘Roma Art’ is thus changing the face of the ways we ‘see’ these minorities, challenging not just stereotypes, but dissembling the power in the ways we see the stereotypes that have mired people in a vortex of hateful practices over hundreds of years.

Continue reading in the article ‘Challenging is not enough: A dialogue with Roma Art’.

Dr Annabel Tremlett is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work in the School of Health Sciences and Social Work at the University of Portsmouth. Twitter: @AnnabelTremlett