In May 2022, the Office for National Statistics reported that 53% of women claim to feel very unsafe walking on their own at night in an open space and as a result, 37% of women admitted to completely avoiding these areas due to fears for their own safety. By critically looking at the ‘Ask for Angela’ campaign, I aim to raise awareness of the normalisation of these fears, and both the behaviour management and societal exclusion of women which has arisen as a result. I have just completed a degree in Sociology and this topic emerged from a final year module which examined emotions in society. I initially presented as an academic poster titled High on Anxiety: A Girl’s Night Out, my research discussed how female fear and male perpetrators can be shaped by gender norms. The ‘Ask for Angela’ campaign, which started in my home county of Lincolnshire, can explain how gender norms could create female fear, at the same time enabling males to react with violence when they feel rejected. While I am writing this piece, teenager Elianne Andam was stabbed to death after challenging her friend’s ex-boyfriend over unwanted advances (Daily Mail, 2023). This story provides a horrific reminder of the culture of male violence and the innocent lives lost as a result.

I begin by highlighting legitimisation of male violence, as a form of ‘everyday violence’ (Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois, 2004). Within a society ruled by a gendered hierarchy, both the actions of male violence itself and the resultant exclusion of women in society, represent forms of everyday violence which have become embedded and normalised. In this context, the everyday violence of a woman’s fear simply becomes ‘terror as usual’ (Taussig, 1989, cited in Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois, 2004), and their reactive behaviours are normalised, representing wider gender inequalities. Influenced by social gender norms, women are constructed as inherently vulnerable and in need of male protection, yet males simultaneously pose as potential dangers. Hille’s (1999) concept of ‘gendered spatiality of fear’ explores how these emotions become gendered, as, in this context, is experienced predominantly by women. Whilst females are constructed as vulnerable, it often falls to women and girls to protect themselves and they are therefore required to manage their behaviour in ways which reduces their risk of male violence. Conceptualised by Lennox (2022) as ‘gendered safekeeping’, this refers to the certain practices and behaviours that women adopt in order to enforce feeling safe. However, importantly, those who are viewed as not appropriately managing their behaviours are blamed for own individual failings and exposing themselves to risk. What is socially determined as ‘risky’ is done so from a masculine lens, creating a double standard as male beliefs are used to scrutinise female behaviour (Walklate, 1998). For example, these arguments commonly appear in rape cases, where women are scrutinised for their behaviours which may have endorsed the sexual violence they experienced. An additional example can be demonstrated in the rise of drink-spiking amongst female university students during 2021, where the police initially demonstrated a slow response and blamed girls for their own drunkenness and individual ‘failures’ (see Townsend and Bryant, 2021; Oppenheim, 2021).

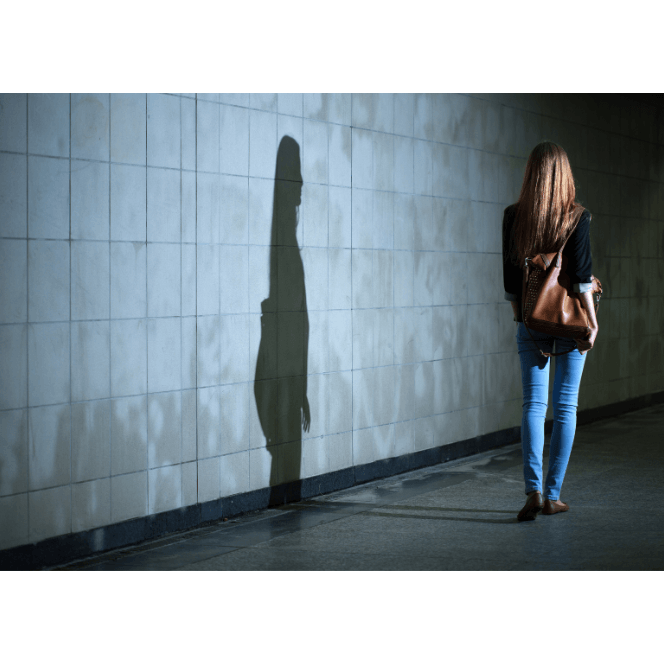

The requirement for women to regulate their own behaviour is directly exampled within the campaign ‘Ask for Angela’, a project initially set up by Lincolnshire County Council in order to support vulnerable women in public spaces. This campaign is commonly advertised through posters in women’s bathrooms, offering a discreet system for women to alert staff at a venue that they need assistance. This can represent a form of ‘gendered safekeeping’ (Lennox, 2022), as women are made aware of practices that they can utilise to keep themselves from harm. Interestingly, the posters commonly refer to arranging transport or using back exits for the women in order to remove them from the situation. However it is clear that it is the behaviour/practices of women which are being managed, rather than the ‘perpetrator’ or the danger. The prevalence of this campaign, and others which are similar, provides a subconscious reminder to women that they should be cautious around events such as first dates, and may further fuel fear and anxiety which surround these events and their potential consequences. Whilst it may sound extreme to some, the regulation of the behaviour of women in accordance to fears of male violence leads to both conscious and subconscious decisions by females to avoid certain public spaces. A spatiality of fear is created when night becomes associated with danger and vulnerability (Valentine, 1992), and in the act of a woman’s rejection toward male advances. This gendered spatial exclusion reminds women of their subordinate position in society, and women are commonly taught that the safest space for them is the home. Whether a conscious individual decision or that made for them by others, women, as a result of male violence, are forced to “trade their freedom for safety” (Vera-Gray, 2018, p.18).

Women’s fear of male violence manifests itself in their everyday lives, so much so, that as a result of the perceived risks to their safety, they may (sub)consciously act in ways which exclude them completely from the public arena. The regularity and normalisation of this fear leads male violence to potentially be understood as everyday violence and allows the resultant behaviour management of females go unnoticed. Yet, should a woman not conform to suitable behaviour-management, she is blamed for any experiences which may occur as a result. As a form of gendered safekeeping, a woman’s decision to remain indoors as a form of protection is not discouraged from society and, consequently, the subordination of women in public space increases, paving the way for wider male domination. But women have become forced to make a choice: lose their freedom or risk their safety.

References

- Daily Mail (2023) ‘Elianne Andam, 15, ‘was chased by masked teenager and stabbed in the neck with a kitchen knife on her way to school after she tried to take her friend’s teddy bear off him’’, Daily Mail Online. Available online: Elianne Andam, 15, ‘was chased by masked teenager and stabbed in the neck with a kitchen knife on her way to school after she tried to take her friend’s teddy bear off him’ | Daily Mail Online [Accessed 5th October 2023]

- Hille, K. (1999) ‘‘Gendered Exclusions’: Women’s Fear of Violence and Changing Relations to Space’, Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 81(2), pp.111-124

- Lennox, R.A. (2022) ‘“There’s Girls Who Can Fight, and There’s Girls Who Are Innocent”: Gendered Safekeeping as Virtue Maintenance Work’, Violence Against Women, 28(2), pp.641-663

- Sabin, L. (2021) ‘Nearly half of women trust police less after Sarah Everard murder, survey suggests’, The Independent. Available online: Nearly half of women trust police less after Sarah Everard murder, survey suggests | The Independent [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Scheper-Hughes, N. and Bourgois, P. (2004) ‘Introduction: Making sense of violence’, in Bourgois, P. and Scheper-Hughes, N. (eds.) Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology. Oxford: Blackwell Press, pp.1-31

- Valentine, G. (1992) ‘Images of Danger: Women’s Sources of Information about the Spatial Distribution of Male Violence’, Area, 24(1), pp.22-29

- Vera-Gray, F. (2018) The Right Amount of Panic. How women trade freedom for safety. Bristol: Policy Press

Amy Sanderson is a recent Sociology graduate from the University of Liverpool, with academic interests in the sociology of health and gender, feminism and class. During her time at University, Amy was on the committee of the Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology Society, which she did alongside playing netball and exploring the new city with her friends. She has since moved home to begin her career and is grateful to her family and friends for their continued support.